Citroën has consistently moved the engineering, styling and marketing of cars forward, occasionally down blind alleys such as the rotary-engined GS project, but more usually into technological breakthroughs that the industry copies or even licenses from them. The 2CV fits into that tradition perfectly.

Always different, but always comfortable, logical and beautiful.

From the very start, Citroën products were never conservative and always distinctive. Robert Opron’s masterful 1968 ‘Nouveau Visage’ facelift of the DS only improved on Flaminio Bertoni’s original design and previewed themes which would appear on his later masterpiece, the SM. The styling of certain cars, such as the BX or Ami 6, has divided opinion, but they could not have originated from any other manufacturer. The rear was, perhaps, the Ami 6’s best angle. Designed by Flaminio Bertoni, it was less popular than his other designs, but, surprisingly, he considered the Ami 6 to be his masterpiece.

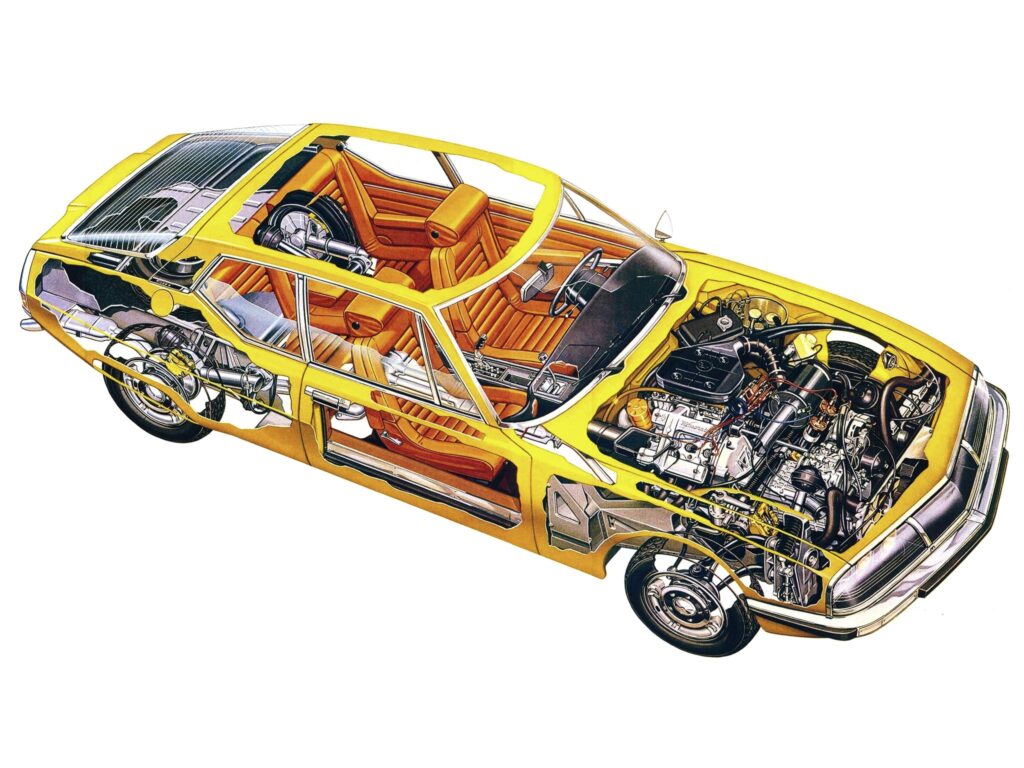

Those double chevrons have, however, continually appeared on the front of interesting, individual, but intensely logical cars, which had no truck with conventional wisdom. Those cars have included a genuine candidate for the most beautiful car ever designed – the SM. Contenders for that epithet tend to come from companies that make expensive sports cars, such as the Jaguar E-type, Ferrari GTO or Lamborghini Miura. Citroen’s ambitions in the 1960s were so broad, however, that they bought Maserati and installed their sonorous Italian V6 in this outrageously beautiful front-wheel-drive coupe that used the DS’s unique suspension and steering systems, while the company was still making a range of economy and family cars and commercials as well.

They also produced the greatest single technological leap ever made by the motor industry – the DS, a car which still made most cars look out of date ten years after it was launched.

Yet, the two cars above were contemporaries of the purest interpretation of the word car, a machine in which to move people, things and animals, as comfortably and economically as possible, ever made – the 2CV. Those three cars alone show a greater range than most manufacturers could ever have considered.

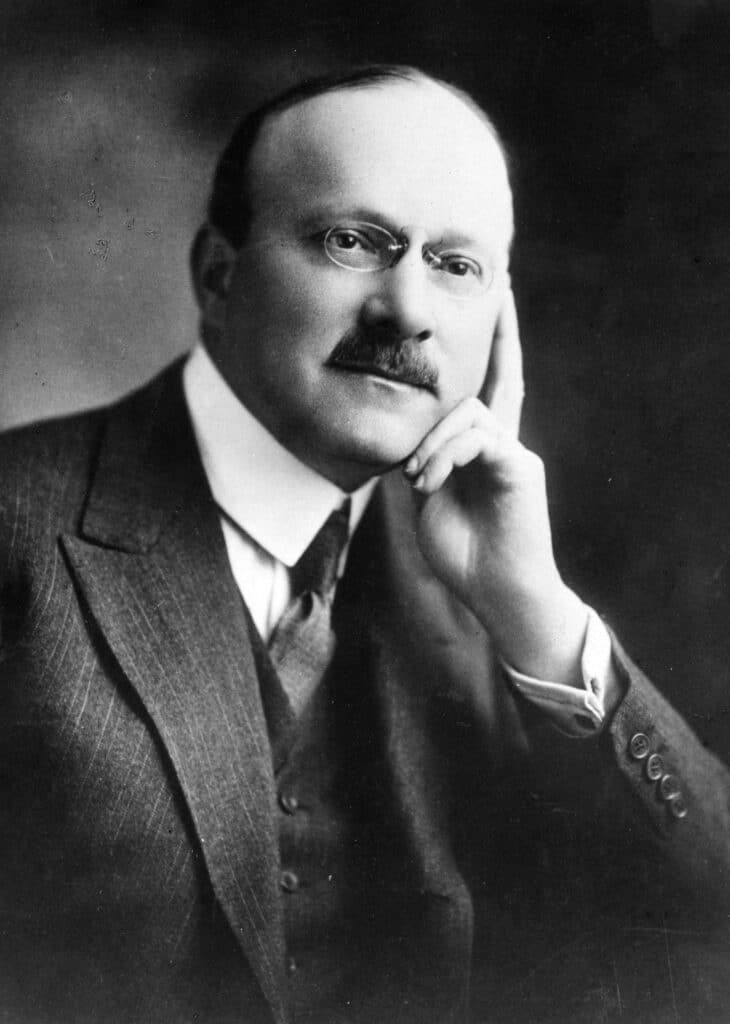

Andre Citroën

André Citroën was born in Paris in 1876 and was far more than merely the ‘French Henry Ford’. He was very gifted and had an extraordinary multifaceted talent for lateral thinking. He also possessed a great flair for the dramatic and had a relentless creative energy and ambition that, perhaps, helped him into an early grave, sadly. He did not only pioneer car production techniques but also invented new ways to advertise his cars, which were, in their way, more radical and far sighted than the cars themselves, at least initially; only Citroën would have thought of having an aircraft write his name in smoke letters over Paris during the 1922 Motor Show, or giving the nation 150,000 sponsored road signs so you were reminded of Citroën when driving to a new uncertain destination, or turning the whole of the Eiffel Tower into a giant beacon saying Citroën, which Charles Lindbergh used as a sighting beacon before landing after completing the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

Citroën’s initial business was making double helical teeth gears (the origin of the double chevron badge), and his success in this gave him the capital to create his eponymous car company. His first car, the Type A, was launched in 1919, but it was the 1922 856cc Type-C 5CV, or ‘Cloverleaf’, which really started to motorise France; 80,759 were built before it was replaced in 1926. It may only have been made for 4 years, his restless energy to continually improve saw to that, but it has much the same cultural significance in France as the Austin 7 does in the UK and sprang from a similar design brief, build a proper car in miniature. Despite great popularity, the ‘Petite Citron’ (Little Lemon), a nickname derived from the fact that many were yellow, became a victim of progress and production ceased in May 1926.

The Attraction of the Traction

Citroën continued to grow through the 1920s, and in 1934, it shocked the world with the Traction Avant. It was lower and lighter than any of its competitors because the pioneering monocoque construction and unique front-wheel drive layout allowed the body to be wrapped around the components, yet remain a stiff and lightweight structure. There were no tunnels to clutter the interior’s comfort either.

Engineer André Lefèbvre had produced a car that pioneered monocoque all-steel construction and front-wheel-drive, but it sold because stylist Flaminio Bertoni had produced a shape so strikingly elegant that it became an icon of style as well as avant-garde engineering. Remarkably, it remained in production until 1957, by which time 759,123 examples had been built. It may seem like a quintessential French product, and in many ways, it was, but Traction Avants, DSs and 2CVs were also built in a factory Citroën opened in Slough in 1926 and would continue to use until 1966. Perhaps Sir John Betjeman wasn’t aware of this, or the extent to which Citroëns had woven themselves into the creative tapestry of Europe, when he wrote that famous poem?

Sadly, although the Traction Avant was a technical and sales success, its development had taken its toll on both the company and the man. André Citroën passed away in July 1935, just after he had seen his company taken over by Michelin, the firm’s main creditor. Citroën was, however, by then the biggest car company in Europe, and, remarkably, the second biggest in the world. They needed reorganising, though, as the focus had become the making of great, interesting, avant-garde and charismatic vehicles, not money. No commercial enterprise can do that forever.

The new era.

Citroën, however, continued on their pioneering path under the new ownership and shocked the world again by launching what must surely be the most futuristic mass-market car ever envisaged, the DS.

This little piece of advertising genius was an attempt to explain that the DS rode on a liquid suspension. It’s not a painting; the advertising team actually built the whole thing and anchored it in place for the photography.

Another beautiful but aerodynamic Bertoni shape, clothed a car of such breath-taking engineering sophistication, it appeared to have been dropped into 1955 from the future. The interlinked hydropneumatic suspension gave a magic-carpet ride of seemingly impossible comfort and it offered a host of other breakthroughs. The DS also proved a very successful rally car, a sport the company has done consistently well in since, and it set the template for large Citroens for decades to come.

It even gave its hydropneumatic technology to cars as diverse as the Maserati Khamsin, one of Marcello Gandini’s great styling masterpieces, and the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow/Bentley T2.

In part two, we’ll look at how the 2CV stacked up against the world’s great utilitarian economy cars.

Pictures:

Citroën/Stellantis

Fiat Citroën/Stellantis

Maserati/Stellantis

Rolls-Royce

London Classic Car Show