The foundations for the eventual takeover of Grand Prix racing by the two-strokes from Japan in the 1970s were actually laid in Germany four decades earlier. For, without doubt, the DKW designs of the 1930s were the most significant in the entire history of the two-stroke engine. Every major component of two-stroke technology throughout the 20th century (from rotary disc intake valves to flexible inlet reed valves that functioned through their reactions to fluctuations in internal engine pressures) can be traced back to the talents of the designers and engineers at DKW in the years before World War II.

advertising poster for DKW Auto Union motorcycles circa 1930. Artist unknown, 1931 (Photo by Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images)

At that time, DKW was the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world with a 20,000-strong workforce and over 200,000 machines made since production began in 1926.

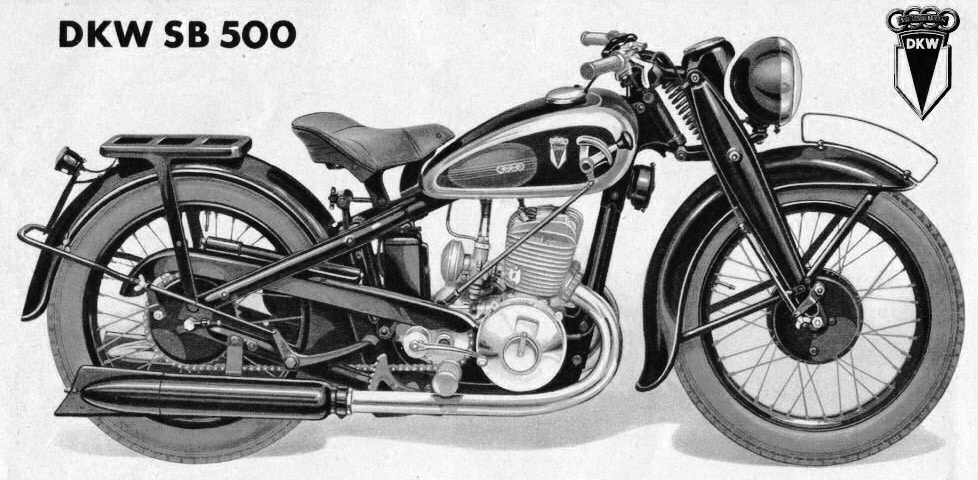

Machines like the SB500 were strong sellers; it was launched in 1934 and remained in production until 1939, by which time approximately 19,000 had been built. Its twin-cylinder two-stroke 494cc engine produced around 15bhp and was connected to a three-speed hand-change gearbox operated by a foot clutch. It also had ‘Dynastart’ electric starting and was one of the first bikes to offer this feature. It was a bike ahead of its time.

Its significant contribution to motorcycling history was, however, the simple RT125, which after WWII was part of Germany’s war reparations to the Allied nations and was manufactured in the UK as the now-legendary BSA Bantam.

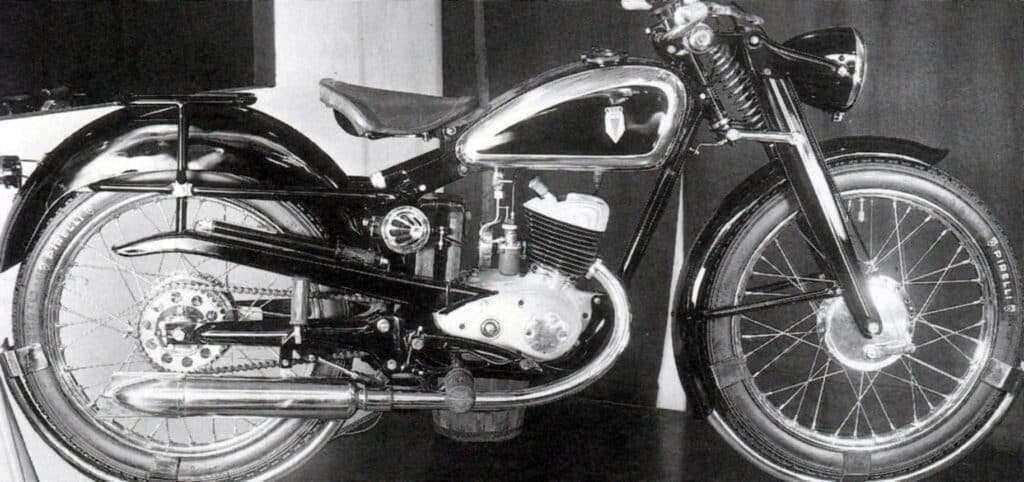

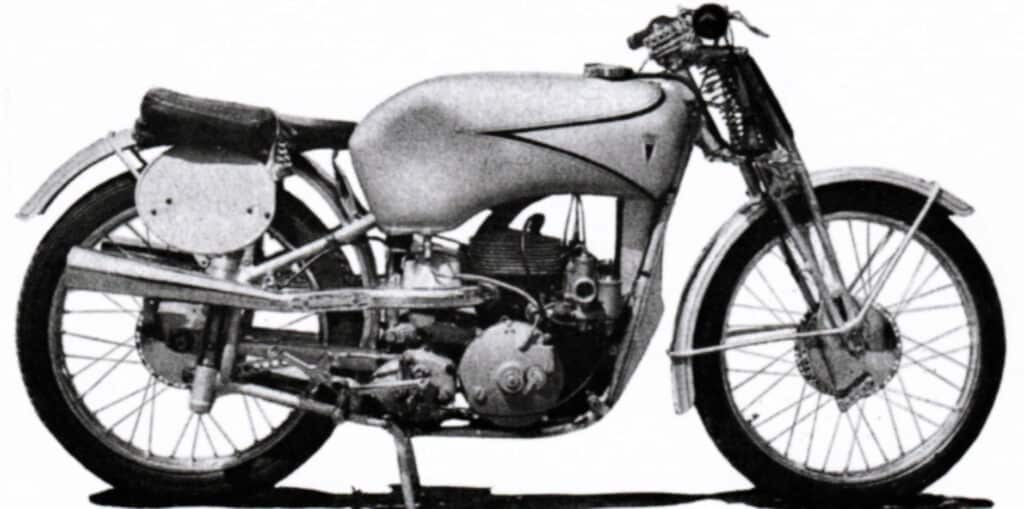

Instantly recognisable as what became the ubiquitous BSA Bantam in 1950s Britain, this 1937 DKW RT125 was the most-copied motorcycle ever. It was reproduced in countries including Russia, several Eastern European communist nations, India, the USA and Japan.

The DKW RT125 engine was superb in its simplicity, but the machine that Ewald Kluge rode to victory in the 1938 250cc TT was perhaps the most complex two-stroke designed, even when compared to the ultimate examples of the technology in the final decade of the 20th century.

The 1938 DKW 250 that Ewald Kluge rode to a dominating victory in the Isle of Man TT

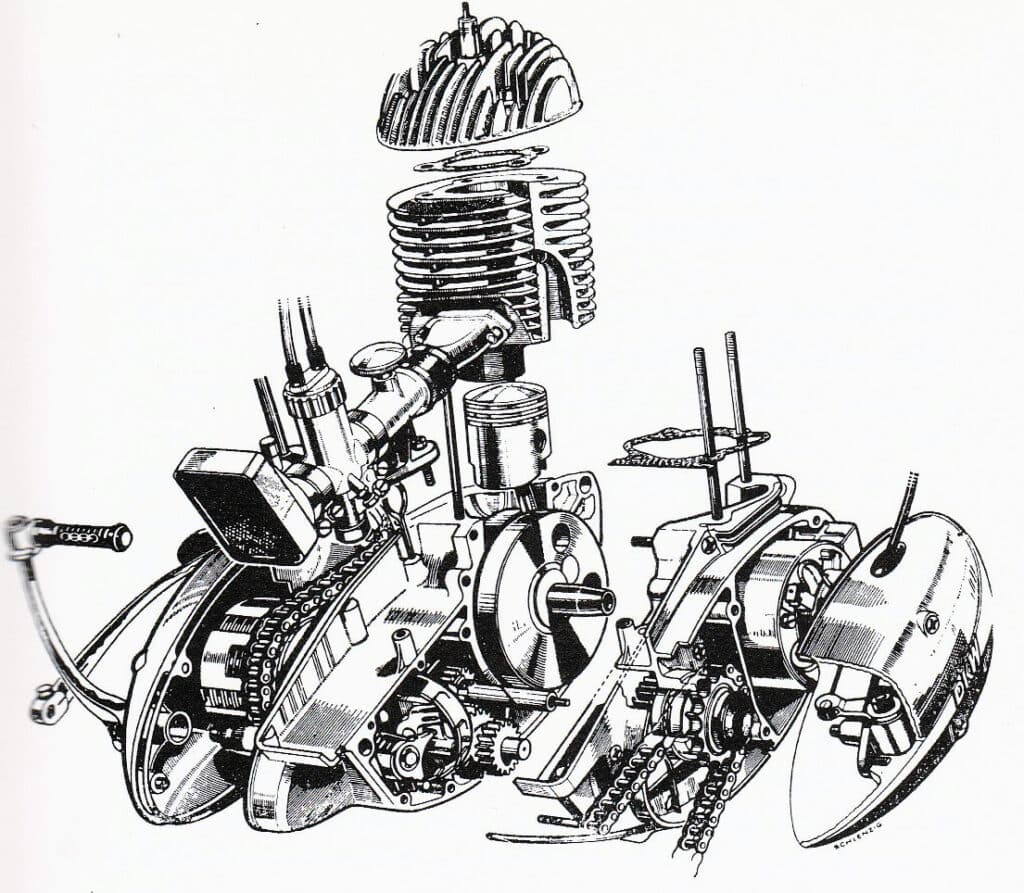

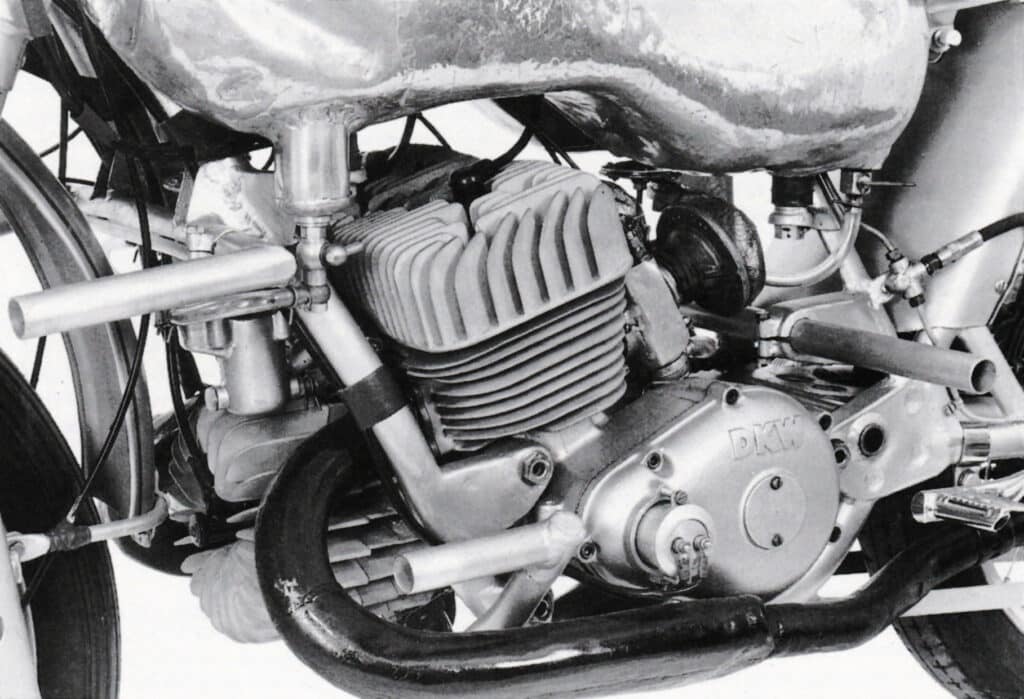

At first glance, with its two carburettors and two exhaust pipes, it appeared to be a conventional twin but closer inspection proved more puzzling. First of all, there was only a single spark plug in the cylinder head, which revealed that it was, in fact, what was termed a ‘split single’ with two cylinders fired in a common combustion chamber.

But then there was what seemed to be another cylinder, albeit with no spark plug, that was positioned horizontally ahead of the main engine block. That cylinder was the secret of the engine’s power as it was, in fact, a built-in form of supercharging!

The two carburettors were positioned at each end of a rotary valve, but this was not the more familiar crankshaft-mounted slotted disc seen on the successful GP two-strokes of the 1960s. It was actually a horizontally and transversely-mounted cylindrical barrel geared to the crankshaft and was slotted so as to deliver a precisely-timed fuel/air charge into the horizontal non-sparking cylinder

This had a larger piston than the two in the main engine block and functioned purely as a means of compressing the intake charge. It delivered the same result as a supercharger with the compressed fuel/air mixture effectively giving a ‘bigger bang’ when fed back via transfer ports into the crankcase for the engine’s two main cylinders and for ignition and combustion by the single spark plug in the cylinder head. This type of engine was what was termed a ‘split single’ and was one of many early two-stroke designs aimed at achieving the holy grail of complete combustion of the fuel/air intake charge and the total scavenging of the crankcase, ready for the process to begin again.

In the 1938 TT-winning DKW, it was one part of a total design package that proved to be unbeatable. When he took the chequered flag, Kluge was over ten minutes clear of his closest rival!

A 1954 brochure for DKW’s cars.

In the immediate post-war years, the victorious Allied nations divided Germany into two separate countries with very different political philosophies. West Germany remained politically independent, but East Germany was a communist country very much influenced by the Soviet Union. One effect of this division was to split what had been the world’s largest motorcycle company. The giant DKW factory at Zschopau in the former province of Saxony was marooned in East Germany behind what Winston Churchill had described as the “Iron Curtain” that divided Europe’s western nations from the Soviet-controlled countries to the east. As a result of this, the motorcycle activities of the DKW brand were moved west to Ingolstadt in Bavaria, the home of the Auto Union group of car manufacturers, of which DKW had been a major component since 1932 by its merger with the Audi, Horch and Wanderer car brands.

From its new home in West Germany, DKW continued to make its single-cylinder 125cc motorcycles as well as 250cc & 350cc twins and cars with 900cc three-cylinder two-stroke engines until the Auto Union group decided to cease motorcycle production in 1959 and consigned one of the world’s most famous marques to history.

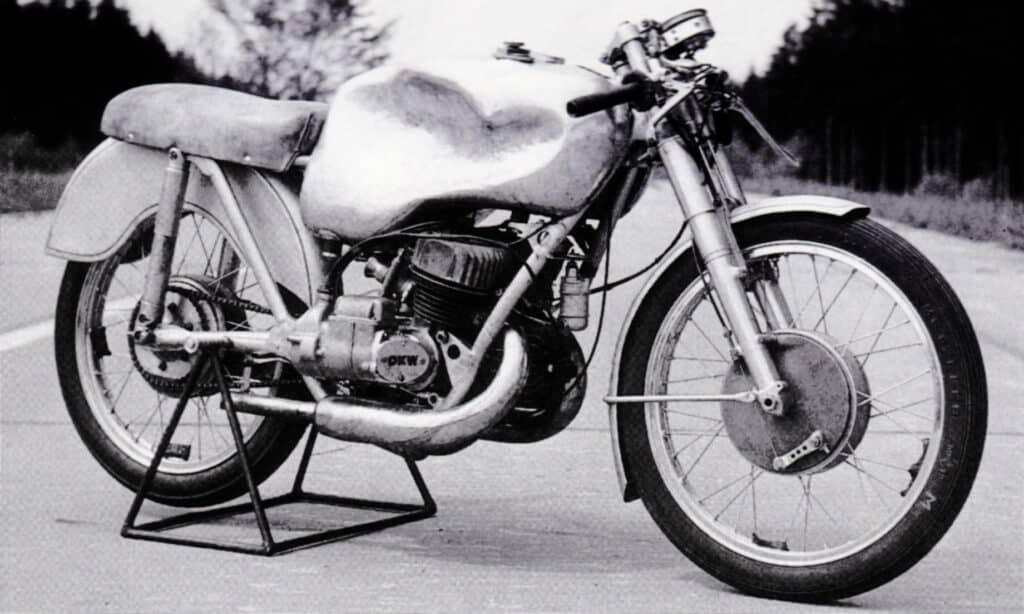

The initial prototype of the DKW 350cc triple was first seen in 1952

Prior to that, DKW continued a racing programme from the early 1950s with uprated versions of their conventional road-going two-strokes and also reworked the design of their pre-war engines to come up with a three-cylinder, two-stroke 350cc racer. This followed the architecture of the TT-winning 250 but, with all forms of supercharging having been excluded by the post-war Grand Prix rules, it now used the original horizontal ‘pumping cylinder’ location to accommodate a third working cylinder. Unlike its dominant predecessor, it followed the conventional two-stroke practice of using the piston’s position to control the induction, combustion, and exhaust processes in the individual cylinders.

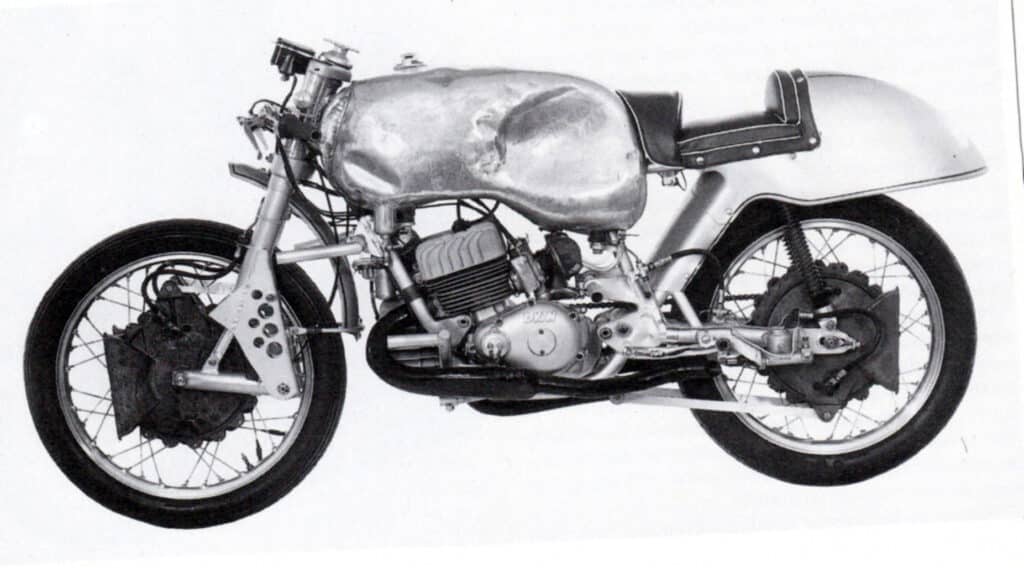

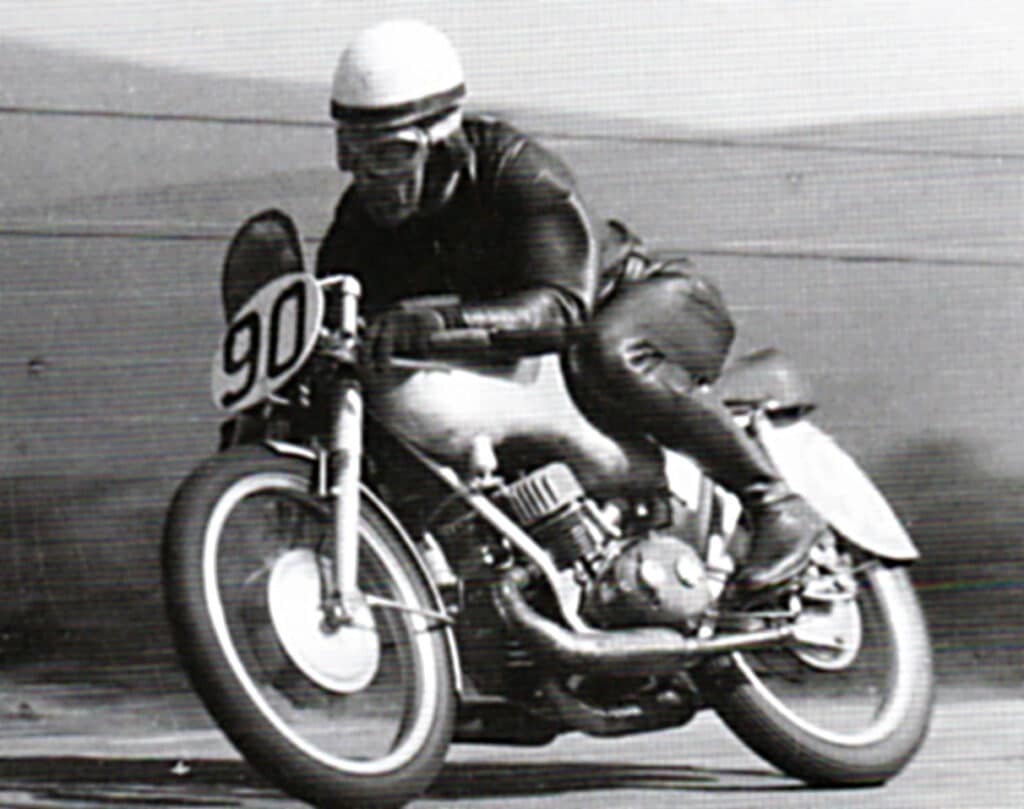

In its final 1955/56 form, the DKW 350cc triple was a genuine Grand Prix contender

In that form, it was fast, but not quite fast enough to beat the Italian single-cylinder four-strokes from Moto Guzzi. Even so, and despite never winning a Grand Prix, August Hobl took the DKW two-stroke to third place in both the 1955 and 1956 World 350cc Championships, finishing behind the Moto Guzzi team riders, Bill Lomas and Dickie Dale, in each of those seasons.

That was the end of an era in Grand Prix competition as DKW joined all of the Italian factories apart from MV Agusta (the privately-funded passion of Count Domenico Agusta) in pulling out of racing due to the economic climate of the mid-1950s.

While motorcycles were still sold with the DKW badge for another two years afterwards, its proud years as a company with a tremendous racing pedigree were over. It had built an estimated 520,000 motorcycles after WW2, and had once been the largest motorcycle company in the world, but now the brand is generally forgotten by all but classic bike enthusiasts. So it is indeed fitting that we should all be reminded of DKW’s achievements and the legacy that the brand bequeathed to the history of motorcycling.

After the end of World War II in 1945, DKW started producing bikes again. When production ceased in 1959, DKW had made over half a million stylish and superbly engineered two-stroke road bikes like this RT250 single